It’s hard to succeed in school when you miss a lot of classroom time. Students who are suspended out of school or expelled are as much as 10 times more likely to drop out of high school. Students who are excluded from school are also more likely to have contact with the criminal justice system. This effect is so pronounced and widespread that it has a name: the school to prison pipeline.

In Washington, special education students are among the most at risk of being funneled into the school to prison pipeline because schools in our state suspend or expel them at a rate more than double the rate of discipline for their non-special education peers. Often, these students are punished for behaviors that are manifestations of their disabilities— conditions they cannot control.

It’s not just formal discipline; students are pushed out of school in insidious ways. Schools may persuade parents of special education students to agree to shortened school days for their children, depriving them of vital classroom instruction. Students with disabilities may spend a portion of a school day outside of class, in a hallway or another classroom, where they don’t participate in lessons. And parents of students with disabilities may get frequent calls to pick up their child from school as early as the first hour of the school day.

Over the past year, the ACLU of Washington has collected stories from dozens of parents who say their children were punished, excluded from the classroom, and pushed out of public schools in Washington for behaviors stemming from the child’s disability. Here are some of the stories they shared with us.

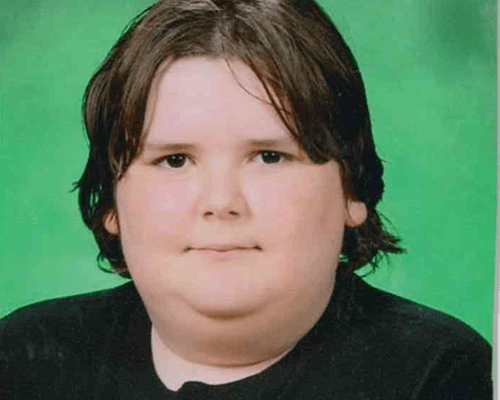

Christian: Punished and forced into online school for taking too long in the restroom

Christian used to love going to school in the Yakima School District, but now he takes classes online, and has little social interaction through school. Christian’s grades have improved, despite the fact that he has never met his teacher, but online education was not his first choice. Christian was forced out of the Yakima School District, where he still lives, by teachers and administrators who punished him for his disability.

Christian suffers from depression and anxiety disorder, as well as encopresis, which means he struggles with knowing when to go to the bathroom. Christian’s condition means he often had accidents that required him to leave the classroom and change clothes. Christian’s school, Hoover Elementary, did not have a shower for Christian to use, so Cary, his father, would have to come pick him up and walk him home, where Christian could shower and change. Rather than feeling supported during these embarrassing incidents, Christian was reprimanded for leaving school. Christian began to suffer from feelings of depression and anxiety as a result.

On one especially traumatic occasion, Christian was blamed for an incident at school where someone had smeared feces on the wall of the boy’s bathroom. Christian was not responsible, but a school bully in his class told administrators Christian did it. Rather than investigating the issue, the school immediately blamed Christian and forced him to clean up the boys’ bathroom. Christian’s parents were never notified about the incident, and only found out after the fact from Christian.

Christian’s depression and anxiety worsened as a result of his treatment at Hoover Elementary, and he fell behind in his school work. School officials incorrectly diagnosed the issue as ADHD, and told Christian’s parents that he needed to take Ritalin. The prescription only worsened Christian’s symptoms, and he had an even harder time focusing at school.

On multiple occasions, school administrators told Cary that he should “just keep Christian home for a few days.” Finally, school administrators told Cary they could not accommodate him at Hoover and that Christian should transfer to McClure Elementary, despite the fact that McClure is miles away from Christian’s home. Christian’s parents did not want to fight to stay in a school that didn’t want to educate their son, so, they agreed to the transfer.

Christian started his 4th grade year at McClure Elementary. Despite high hopes for a better school environment, Christian faced problems straight away. Although McClure had a shower which would help accommodate his encopresis, it was being used as a storage room. The school made Christian clean out the room himself before he could use it. When Christian left class to deal with his encopresis, his teacher told him in front of the whole class he was taking too long. If Christian did not return quickly enough, or did not return before the end of the day, he was punished with detention.

Christian’s peers teased him mercilessly, perpetuating his depression. During a parent-teacher conference, Christian’s teacher was so annoyed that Christian’s desk was messy that she ordered him to dump the desk out on the ground, get down on his hands and knees, and re-organize it. Cary refused to allow him to do this, but Christian was still embarrassed by his teacher’s request.

The principal and school psychologist at McClure strongly suggested that Cary should sign up his son for online schooling. However, when Cary attempted to do so, he found the Yakima School District online education system was not yet set up. When Cary called the school to resolve the issue, an administrator told Cary they would get back to him. That was over a year ago.

In Washington, special education students are among the most at risk of being funneled into the school to prison pipeline because schools in our state suspend or expel them at a rate more than double the rate of discipline for their non-special education peers. Often, these students are punished for behaviors that are manifestations of their disabilities— conditions they cannot control.

It’s not just formal discipline; students are pushed out of school in insidious ways. Schools may persuade parents of special education students to agree to shortened school days for their children, depriving them of vital classroom instruction. Students with disabilities may spend a portion of a school day outside of class, in a hallway or another classroom, where they don’t participate in lessons. And parents of students with disabilities may get frequent calls to pick up their child from school as early as the first hour of the school day.

Over the past year, the ACLU of Washington has collected stories from dozens of parents who say their children were punished, excluded from the classroom, and pushed out of public schools in Washington for behaviors stemming from the child’s disability. Here are some of the stories they shared with us.

Christian: Punished and forced into online school for taking too long in the restroom

Christian used to love going to school in the Yakima School District, but now he takes classes online, and has little social interaction through school. Christian’s grades have improved, despite the fact that he has never met his teacher, but online education was not his first choice. Christian was forced out of the Yakima School District, where he still lives, by teachers and administrators who punished him for his disability.

Christian suffers from depression and anxiety disorder, as well as encopresis, which means he struggles with knowing when to go to the bathroom. Christian’s condition means he often had accidents that required him to leave the classroom and change clothes. Christian’s school, Hoover Elementary, did not have a shower for Christian to use, so Cary, his father, would have to come pick him up and walk him home, where Christian could shower and change. Rather than feeling supported during these embarrassing incidents, Christian was reprimanded for leaving school. Christian began to suffer from feelings of depression and anxiety as a result.

On one especially traumatic occasion, Christian was blamed for an incident at school where someone had smeared feces on the wall of the boy’s bathroom. Christian was not responsible, but a school bully in his class told administrators Christian did it. Rather than investigating the issue, the school immediately blamed Christian and forced him to clean up the boys’ bathroom. Christian’s parents were never notified about the incident, and only found out after the fact from Christian.

Christian’s depression and anxiety worsened as a result of his treatment at Hoover Elementary, and he fell behind in his school work. School officials incorrectly diagnosed the issue as ADHD, and told Christian’s parents that he needed to take Ritalin. The prescription only worsened Christian’s symptoms, and he had an even harder time focusing at school.

On multiple occasions, school administrators told Cary that he should “just keep Christian home for a few days.” Finally, school administrators told Cary they could not accommodate him at Hoover and that Christian should transfer to McClure Elementary, despite the fact that McClure is miles away from Christian’s home. Christian’s parents did not want to fight to stay in a school that didn’t want to educate their son, so, they agreed to the transfer.

Christian started his 4th grade year at McClure Elementary. Despite high hopes for a better school environment, Christian faced problems straight away. Although McClure had a shower which would help accommodate his encopresis, it was being used as a storage room. The school made Christian clean out the room himself before he could use it. When Christian left class to deal with his encopresis, his teacher told him in front of the whole class he was taking too long. If Christian did not return quickly enough, or did not return before the end of the day, he was punished with detention.

Christian’s peers teased him mercilessly, perpetuating his depression. During a parent-teacher conference, Christian’s teacher was so annoyed that Christian’s desk was messy that she ordered him to dump the desk out on the ground, get down on his hands and knees, and re-organize it. Cary refused to allow him to do this, but Christian was still embarrassed by his teacher’s request.

The principal and school psychologist at McClure strongly suggested that Cary should sign up his son for online schooling. However, when Cary attempted to do so, he found the Yakima School District online education system was not yet set up. When Cary called the school to resolve the issue, an administrator told Cary they would get back to him. That was over a year ago.

Court Case:

A.D. v. OSPI