Imagine being awakened in the middle of the night by police, arrested, and ultimately convicted and sentenced to a term of one-three years in prison for the offense of . . . loving the wrong person. This is not a hypothetical scenario from a mythical land. It happened in America, and not too terribly long ago.

June 12 marked the 44th anniversary of a landmark Supreme Court decision and ACLU case, Loving v. Virginia, which held that laws banning interracial marriage were not permissible under the U.S. Constitution.

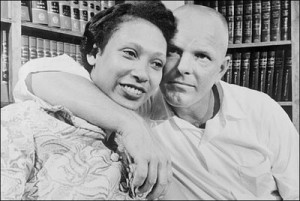

Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving grew up in Virginia, where they fell in love and decided to commit a crime: getting married. Jeter was African American, Loving was white. And Virginia’s “Racial Integrity Act” forbade interracial marriages. The two travelled to Washington, D.C., which had no such prohibition, in order to wed. They returned to Virginia to live.

It was there that they were one night arrested at their home in the middle of the evening (police had timed the meeting in hopes catching the couple in an intimate moment, thereby compounding the gravity of the crime). In 1959 the couple was convicted; the judge agreed to suspend the sentence on the condition that the Lovings leave the state and not return for at least 25 years. The Lovings moved to the District of Columbia, where they continued to face discrimination.

Ultimately, Mildred Loving wrote a plea to then-U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. The attorney general forwarded the letter to the ACLU, which represented the Lovings before the Supreme Court.

From the perspective of 2011, the notion of prohibiting marriage on the basis of skin color is hard to fathom. And for a growing number of Americans, such prohibitions on the basis of gender are beginning to seem just as archaic. Last month, in what the pollsters at Gallup called a “major symbolic milestone,” more Americans polled supported marriage equality than opposed it.

Discussing the historic importance of “Loving Day” on its 40th anniversary in 2007, Mildred Loving eloquently expressed why marriage should be equally accessible to all of us:

Surrounded as I am now by wonderful children and grandchildren, not a day goes by that I don't think of Richard and our love, our right to marry, and how much it meant to me to have that freedom to marry the person precious to me, even if others thought he was the "wrong kind of person" for me to marry. I believe all Americans, no matter their race, no matter their sex, no matter their sexual orientation, should have that same freedom to marry. Government has no business imposing some people's religious beliefs over others. Especially if it denies people's civil rights.

I am still not a political person, but I am proud that Richard's and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness, and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That's what Loving, and loving, are all about.