Published:

Tuesday, November 15, 2022It’s been over two years since the summer of 2020 when sustained protests in Seattle against police violence led to promises from local elected officials to “reimagine public safety,” divest from police, and reinvest into communities to find upstream solutions to prevent crime. Where are we now? Have elected officials made good on those promises? Based on an analysis of the 2022 Seattle Police Department (SPD) budget and the 2023-2024 Proposed SPD Budget, the answer is, resoundingly, no. In fact, we are going backwards, undoing even the meager pandemic era changes that were made.

2023-24 budget negotiations began on September 28, 2022, and will conclude on November 21, 2022, when the City Council adopts the new budget. This is the first biennial budget since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The information below serves to keep you informed about how the City of Seattle is funding policing, as well as other critical services. We will begin with a brief review of SPD’s 2022 budget followed by an analysis of the proposed 2023-24 budget.

SPD’s 2022 Adopted Budget is about $355.5 million. In the 2022 budget cycle, Mayor Durkan and the City Council collectively made about $29.6 million in cuts. Importantly, because of funds added elsewhere in the police budget, the net reduction to SPD’s 2022 budget was about $7.5 million, about a 2 percent cut to the 2021 Adopted Budget of about $363 million. The bulk of the cuts, while meager, went to civilianizing public safety and shrinking the role of the police in our communities. However, they still fell short of divestment from police and reinvestment into community.

The SPD 2022 Adopted Budget consists of a staggering 21.4% of the City of Seattle’s $1.65 billion General Fund (GF), which 42 other departments[1] rely on (at least in part) to fund their operating expenses. Thus, the SPD budget’s share of the GF decreased slightly from 2021 (when it was 22.7% of the GF),[2] but not materially. Funding for police comes overwhelmingly (more than 99%) from the GF,[3] which is taxpayer-generated[4] and is the City’s primary operating budget for all the services it provides. It is a discretionary fund, which means the City Council has flexibility with regard to how it allocates those funds (in contrast to “restricted” funds that must be spent on specific services).

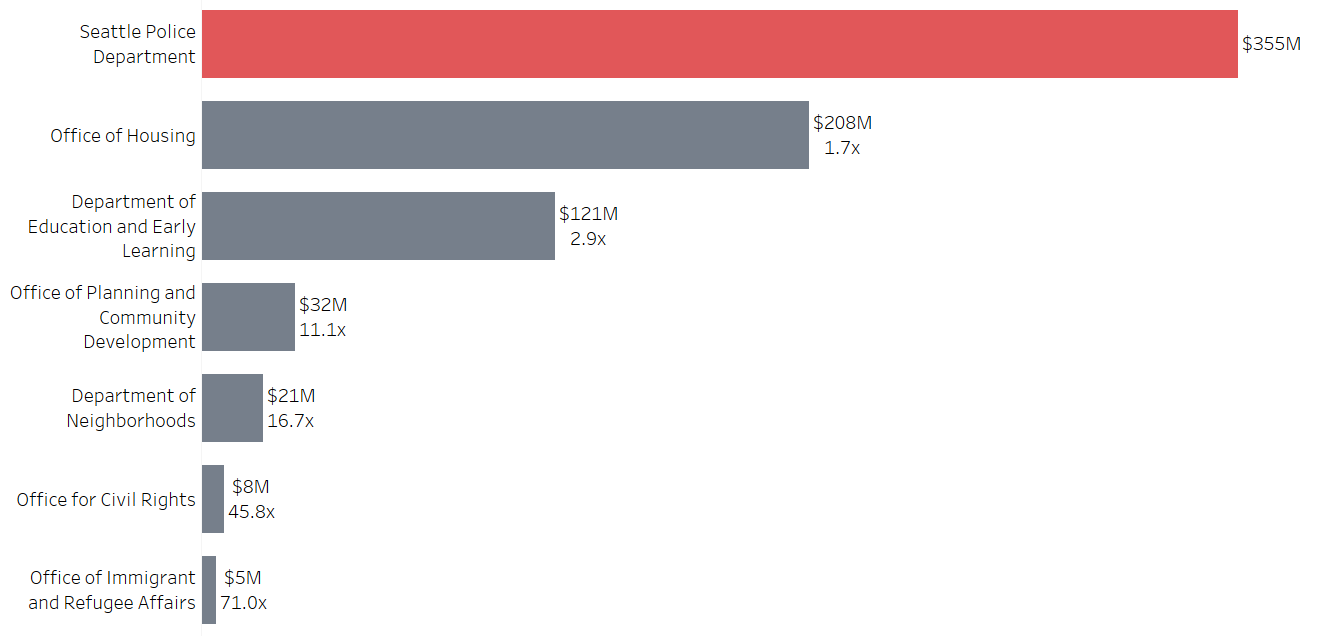

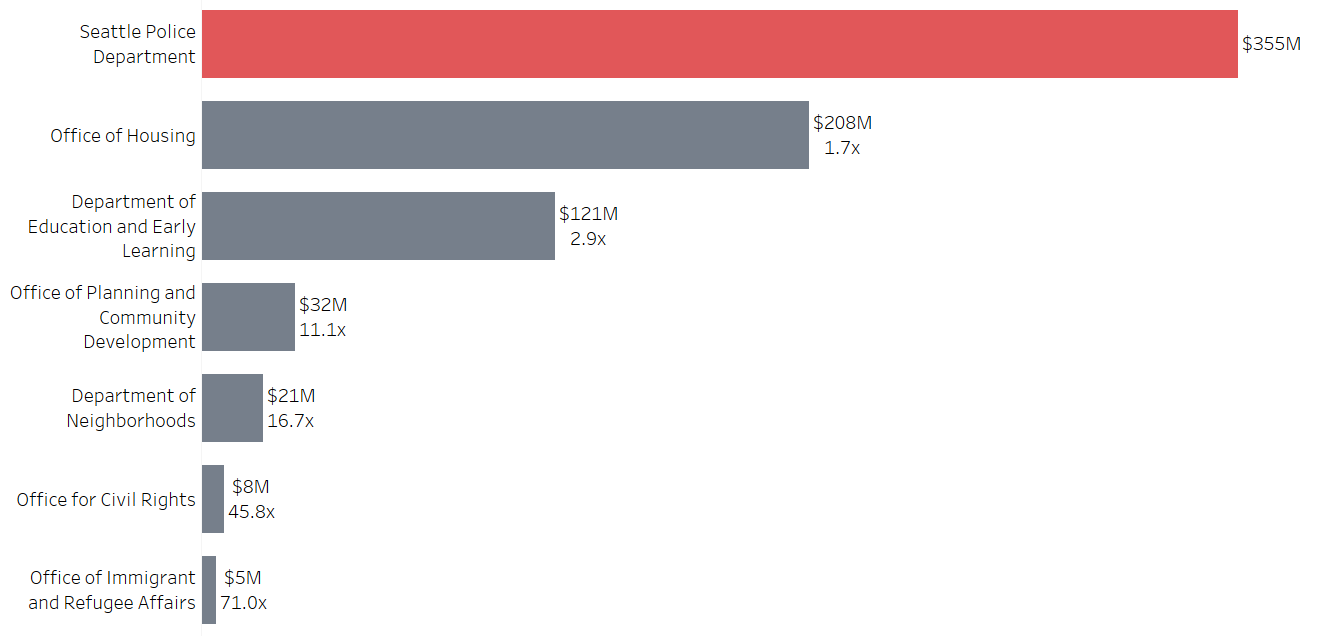

To put it in perspective, compared to the other City of Seattle departments, the SPD budget is (Figure 1):

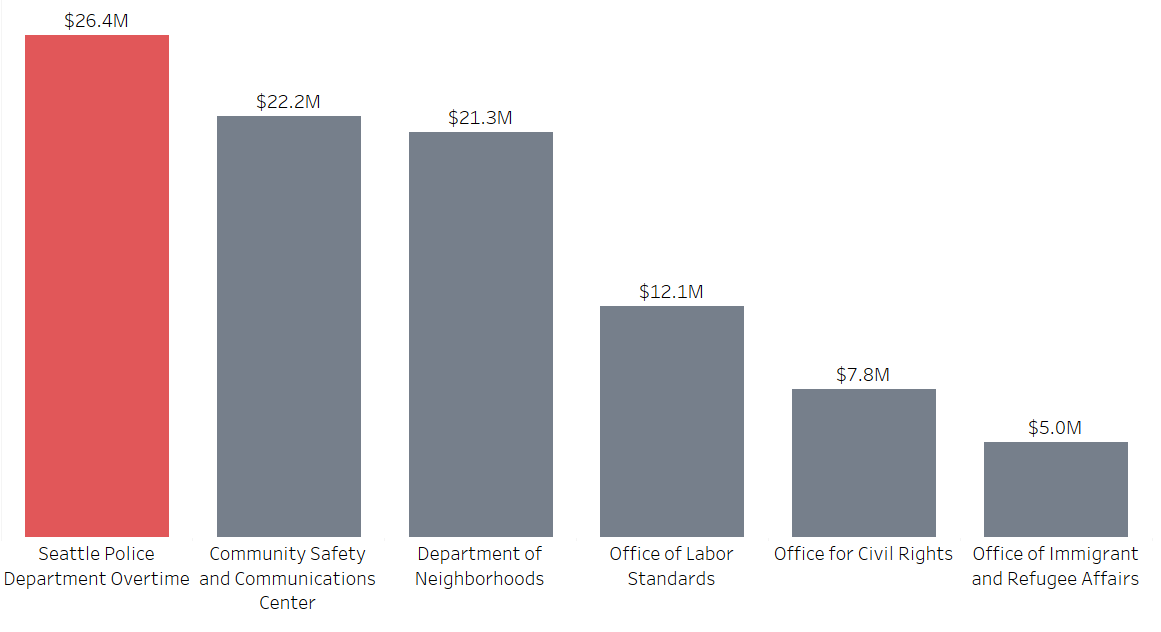

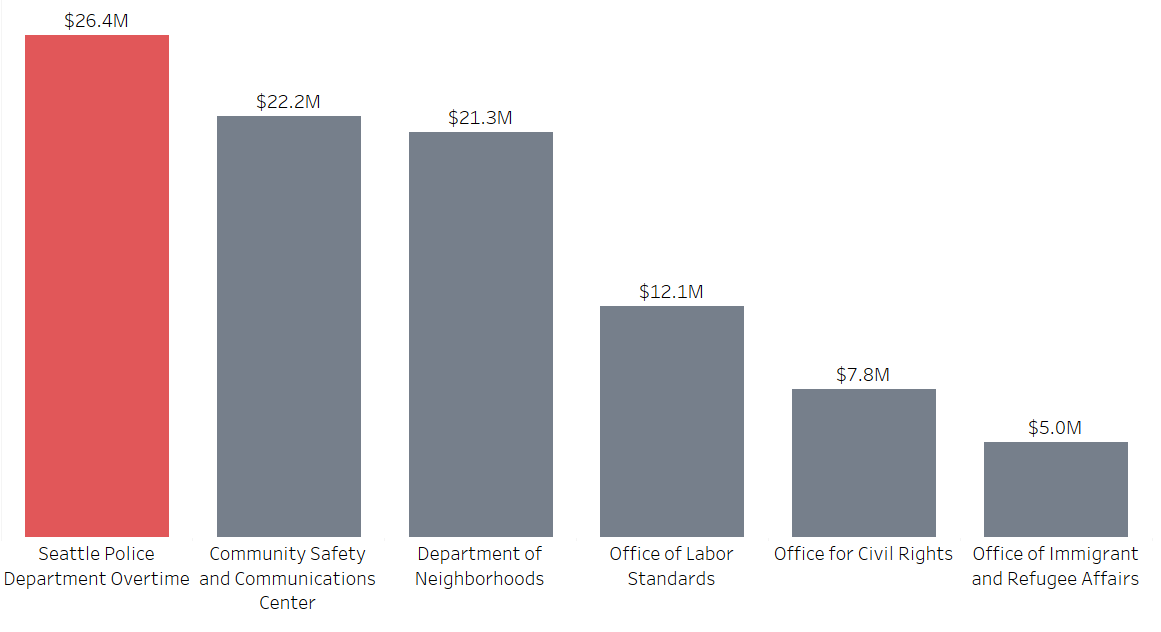

Finally, the SPD’s 2022 budget remains outsized when you consider how much the department is allocated for overtime alone. The overtime budget remains larger than the budgets of more than half (22) of the other City departments funded by the GF, including the Community Safety and Communications Center (CSCC), which was created as part of an effort to “shift away from a police-centric approach to public safety” (see Figure 2). In 2022, SPD’s overtime budget rose almost 17% – from about $22 million to $26.4 million. The overtime budget constitutes a larger share of SPD’s budget in 2022 than it did in 2021 (7.4% in 2022 and 6% in 2021).

Overtime is an important labor tool for compensating workers for the extra time they have worked. However, in the context of policing, its misuse is a systemic problem. Ultimately, as our research shows, the overtime budget alone is substantially larger than most other Seattle departments, and it has become a backdoor way of growing SPD’s budget, with little oversight as to how this money is spent.

The Adopted Budget for SPD also does not reflect all the money that is dedicated to policing on a yearly basis. For example, Money for police misconduct settlements also comes from the General Fund, not the SPD budget. Recent reporting shows that between 2017 and 2021, total payouts for police misconduct statewide rose from $1.15 million to $34.3 million, an increase of almost 3000%.

SPD also proposes to use anticipated “salary savings” (nearly $17 million in 2023 and $12 million in 2024) from 120 officer vacancies to “fund several department priorities”[10] over the next two years. For other City departments, positions that are not planned to be filled are eliminated and the funds go back to the City’s General Fund; the department does not get to keep the funding to spend elsewhere. On the other hand, SPD is proposing that $29 million in unused funding be reallocated to SPD as a slush fund for more police resources and infrastructure in 2023 and 2024, including overtime ($5.2 million) and hiring bonuses ($9.2 million); weapons ($2.1 million); ShotSpotter, an ineffective and inaccurate gun violence reduction technology that disproportionately harms Black and brown communities ($2 million); and public relations programs and strategies that seek to combat SPD’s negative image in the community ($900,000).

The inclusion of a large budget line item for ShotSpotter, a gunfire detection system, is particularly concerning for numerous reasons. As outlined in ACLU-WA’s letter to the City Council, a litany of prominent studies show that ShotSpotter, the most widely used gunfire detection technology, is neither accurate nor effective in reducing gun violence, while disproportionately harming Black and brown communities. It has also led to many wrongful convictions and violence and poses significant surveillance and privacy risks.

Notwithstanding all of these problems, by creating a line item for gunfire detection technology in the SPD budget, Harrell shows his intent to acquire it without first going through proper channels to acquire the technology. As a result, SPD gets the $2 million line item for the technology, and the money sits in SPD’s coffers while the tech must necessarily go through those channels, when that money can be used now to serve critical and urgent community needs.

Critically, ShotSpotter, much like the institution of policing itself, is not a preventive solution to gun violence. It does not address the root causes of gun violence — it only purports to do something after harm has already occurred.

We need upstream, preventive solutions that research shows actually improve public safety by providing economic stability (e.g. emergency financial assistance, guaranteed basic income programs, summer jobs programs); increasing access to healthcare and affordable housing; and improving our neighborhoods (e.g. reducing exposure to pollutants and improving urban planning by providing more green spaces and better access to mass transit). Recently, many of our elected officials in South King County pronounced their support for data-driven solutions to reducing crime and the need to move away from punitive approaches to crime that have proven to be ineffective.

Do you want to keep parking enforcement officers in SDOT to reduce the footprint of police? Do you want the City to use sworn officer salary savings for the expansion of alternative safety models and more city services that actually increase community safety?

You have an opportunity to weigh in on what the SPD budget will look like.

The budget process concludes when the City Council votes to adopt the 2023-24 budget on November 21. November 15th at 5 pm is your last chance to attend a public hearing on the budget (remotely or in-person) and submit your comment to influence the budget. Your written comment can be emailed anytime.

Please turn out and make your voice heard!

2023-24 budget negotiations began on September 28, 2022, and will conclude on November 21, 2022, when the City Council adopts the new budget. This is the first biennial budget since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The information below serves to keep you informed about how the City of Seattle is funding policing, as well as other critical services. We will begin with a brief review of SPD’s 2022 budget followed by an analysis of the proposed 2023-24 budget.

Review of Seattle’s 2022 Policing Budget

SPD’s 2022 Adopted Budget is about $355.5 million. In the 2022 budget cycle, Mayor Durkan and the City Council collectively made about $29.6 million in cuts. Importantly, because of funds added elsewhere in the police budget, the net reduction to SPD’s 2022 budget was about $7.5 million, about a 2 percent cut to the 2021 Adopted Budget of about $363 million. The bulk of the cuts, while meager, went to civilianizing public safety and shrinking the role of the police in our communities. However, they still fell short of divestment from police and reinvestment into community.

The 2022 SPD Budget Remains Outsized According to Several Measures

The SPD 2022 Adopted Budget consists of a staggering 21.4% of the City of Seattle’s $1.65 billion General Fund (GF), which 42 other departments[1] rely on (at least in part) to fund their operating expenses. Thus, the SPD budget’s share of the GF decreased slightly from 2021 (when it was 22.7% of the GF),[2] but not materially. Funding for police comes overwhelmingly (more than 99%) from the GF,[3] which is taxpayer-generated[4] and is the City’s primary operating budget for all the services it provides. It is a discretionary fund, which means the City Council has flexibility with regard to how it allocates those funds (in contrast to “restricted” funds that must be spent on specific services).

Figure 1: SPD Budget Relative to Select City of Seattle Departments, 2022

Source: SPD 2022 Adopted Budget

To put it in perspective, compared to the other City of Seattle departments, the SPD budget is (Figure 1):

- 71 times bigger than the Office of Immigrant and Refugee Affairs

- 46 times bigger than the Office for Civil Rights

- 17 times bigger than the Department of Neighborhoods

- 11 times bigger than the Office of Planning and Community Development

- 3 times bigger Department of Education and Early Learning

- 1.7 times bigger than the Office of Housing

Finally, the SPD’s 2022 budget remains outsized when you consider how much the department is allocated for overtime alone. The overtime budget remains larger than the budgets of more than half (22) of the other City departments funded by the GF, including the Community Safety and Communications Center (CSCC), which was created as part of an effort to “shift away from a police-centric approach to public safety” (see Figure 2). In 2022, SPD’s overtime budget rose almost 17% – from about $22 million to $26.4 million. The overtime budget constitutes a larger share of SPD’s budget in 2022 than it did in 2021 (7.4% in 2022 and 6% in 2021).

Figure 2: SPD Overtime Budget Relative to Select City of Seattle Department Budgets, 2022

Source: SPD 2022 Adopted Budget

Source: SPD 2022 Adopted Budget

Overtime is an important labor tool for compensating workers for the extra time they have worked. However, in the context of policing, its misuse is a systemic problem. Ultimately, as our research shows, the overtime budget alone is substantially larger than most other Seattle departments, and it has become a backdoor way of growing SPD’s budget, with little oversight as to how this money is spent.

The Adopted Budget for SPD also does not reflect all the money that is dedicated to policing on a yearly basis. For example, Money for police misconduct settlements also comes from the General Fund, not the SPD budget. Recent reporting shows that between 2017 and 2021, total payouts for police misconduct statewide rose from $1.15 million to $34.3 million, an increase of almost 3000%.

The 2023-24 Proposed SPD Budget: Broken Promises

For the first time since the summer protests of 2020 spawned widespread calls for racial justice and police divestment, SPD’s budget has increased, reneging on promises they made in 2020 and 2021. Mayor Harrell’s proposed 2023 SPD budget[5] is $375.7 million (an increase of 5.4% from 2022) and the proposed 2024 budget is $385.6 million (an increase of 2.6% from 2023).[6] The increase in 2023 is largely a reflection of transferring Parking Enforcement Officers (PEOs) from Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) back to SPD, reversing a decision made by the City Council in the 2021 budget cycle to move civilian functions[7] out of SPD to thereby reduce the footprint of policing ($20 million). This is troubling given the lack of progress made by the city to create and operationalize non-police safety responses to community needs.[8] Despite the success of systemic alternative safety models in other states — i.e. options for crisis response other than an armed police response — “Seattle’s responses have been limited and ad-hoc, consisting of a patchwork of unrelated programs housed inside the police and fire departments.”[9]SPD also proposes to use anticipated “salary savings” (nearly $17 million in 2023 and $12 million in 2024) from 120 officer vacancies to “fund several department priorities”[10] over the next two years. For other City departments, positions that are not planned to be filled are eliminated and the funds go back to the City’s General Fund; the department does not get to keep the funding to spend elsewhere. On the other hand, SPD is proposing that $29 million in unused funding be reallocated to SPD as a slush fund for more police resources and infrastructure in 2023 and 2024, including overtime ($5.2 million) and hiring bonuses ($9.2 million); weapons ($2.1 million); ShotSpotter, an ineffective and inaccurate gun violence reduction technology that disproportionately harms Black and brown communities ($2 million); and public relations programs and strategies that seek to combat SPD’s negative image in the community ($900,000).

The inclusion of a large budget line item for ShotSpotter, a gunfire detection system, is particularly concerning for numerous reasons. As outlined in ACLU-WA’s letter to the City Council, a litany of prominent studies show that ShotSpotter, the most widely used gunfire detection technology, is neither accurate nor effective in reducing gun violence, while disproportionately harming Black and brown communities. It has also led to many wrongful convictions and violence and poses significant surveillance and privacy risks.

Notwithstanding all of these problems, by creating a line item for gunfire detection technology in the SPD budget, Harrell shows his intent to acquire it without first going through proper channels to acquire the technology. As a result, SPD gets the $2 million line item for the technology, and the money sits in SPD’s coffers while the tech must necessarily go through those channels, when that money can be used now to serve critical and urgent community needs.

Critically, ShotSpotter, much like the institution of policing itself, is not a preventive solution to gun violence. It does not address the root causes of gun violence — it only purports to do something after harm has already occurred.

We need upstream, preventive solutions that research shows actually improve public safety by providing economic stability (e.g. emergency financial assistance, guaranteed basic income programs, summer jobs programs); increasing access to healthcare and affordable housing; and improving our neighborhoods (e.g. reducing exposure to pollutants and improving urban planning by providing more green spaces and better access to mass transit). Recently, many of our elected officials in South King County pronounced their support for data-driven solutions to reducing crime and the need to move away from punitive approaches to crime that have proven to be ineffective.

Take Action Now to Influence the 2023 Police Budget

The Seattle City Council’s amendments to the Mayor’s budget proposal for SPD are minimal, limited to reporting requirements (e.g. for police staffing, overtime, finances, performance metrics). Otherwise, they do not change any line items. However, Councilmember Mosqueda introduced an amendment to eliminate the proposed transfer of the city’s parking enforcement unit.[11]Do you want to keep parking enforcement officers in SDOT to reduce the footprint of police? Do you want the City to use sworn officer salary savings for the expansion of alternative safety models and more city services that actually increase community safety?

You have an opportunity to weigh in on what the SPD budget will look like.

The budget process concludes when the City Council votes to adopt the 2023-24 budget on November 21. November 15th at 5 pm is your last chance to attend a public hearing on the budget (remotely or in-person) and submit your comment to influence the budget. Your written comment can be emailed anytime.

Please turn out and make your voice heard!

[1] In 2022, the City gained one new department, the Department of Economic and Revenue Forecasts, created via Council Bill in 2021, and apparently lost a department— Seattle Emergency Communications Center (SECC). The SECC was added as a new department last year and was intended to be “the primary Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP) for the receipt, triage, and dispatch of public safety services within the City of Seattle” (Seattle Emergency Communications Center, 313). It however did not have a budget line item because it was still in the process of being stood up.

[2] In 2021, $360 million of SPD’s $363 million was from GF revenues.

[3] $353.4 million of SPD’s $355.5 million budget consists of revenue from the GF. The rest of the budget is comprised of funding from the School Safety Traffic and Pedestrian Improvement Fund for the School Zone Camera Program.

[4] Nearly 80 percent of the 2022 General Fund is generated by taxes: property (22.7%), sales (18.5%), payroll (5.2%), business and occupation (19.3%), utility taxes (13.2%), and other taxes (0.9%)..

[5] Page 357

[6] Seattle Police Department 2023-24 Proposed Budget, available at https://www.seattle.gov/documents/Departments/FinanceDepartment/2324proposedbudget/2023-2024%20Proposed%20Budget%20Book.pdf, page 357.

[7] There are two broad categories of officers within SPD. Sworn officers (e.g. police officers) carry a firearm, have the power to make arrests, and carry a badge. They also go through training at the academy. Civilian officers (e.g. 911 dispatch, parking enforcement) do not have these characteristics.

[8] E.g. “Seattle Was Supposed to Create Alternatives to Police for 911 Calls. What Happened?” available at https://publicola.com/2022/07/13/seattle-was-supposed-to-create-alternatives-to-police-for-911-calls-what-happened/; “Harrell’s Budget Would Move Parking Enforcement Back to SPD, Add $10 Million to Homelessness Authority, and Use JumpStart to Backfill Budget,” available at https://publicola.com/2022/09/27/harrells-budget-would-move-parking-enforcement-back-to-spd-add-10-million-to-homelessness-authority-and-use-jumpstart-to-backfill-budget/ (“Although Harrell’s office has said they plan to stand up a new ‘third’ public safety department starting in 2024, the budget does not include any specific line times for work to develop this department next year.”)

[9] “Seattle Was Supposed to Create Alternatives to Police for 911 Calls. What Happened?,” available at https://publicola.com/2022/07/13/seattle-was-supposed-to-create-alternatives-to-police-for-911-calls-what-happened/

[10] Seattle Police Department, “2023 and 2024 Proposed Budget Overview,” available at http://seattle.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=11300538&GUID=51744ABE-D8F3-4965-BC8C-B9E1257234C8 (pp. 2-8)

[11] See SDOT-020-A-001-2023, available at https://www.seattle.gov/council/issues/understanding-councils-budget-amendments.

Explore More: