Published:

Monday, May 24, 2021By Kendrick Washington, ACLU-WA Youth Policy Counsel and Tori Hazelton, ACLU-WA Policy Advocacy Intern

As the national discourse around policing grows, it is imperative that the conversation include a frank and open discussion about School Resource Officers (SROs) and explore the question: Do we need police in schools? SROs, also known as Campus Resource Officers (CROs) are commissioned law enforcement officers with sworn authority to make arrests, deployed under the auspices of a need for community-oriented policing in K-12 school districts. While SROs first began appearing in schools nearly 40 years ago, they proliferated during the 1990s after the shooting at Columbine and continued to increase after more recent tragic events such as Sandy Hook and Parkland. Fueled by a 24-hour news cycle and social media, the idea that our youth are more incorrigible, more criminal, and more violent has intensified the cries for police presence in schools. The truth of the matter is that mass shootings at schools are very rare,[1] and SROs do not prevent or stop them. In fact, research shows that the presence of SROs is detrimental to the welfare of our children, leading to the increased criminalization of youth for child-like behaviors. This blog post examines whether police actually make our schools safer.SROs have not prevented or stopped mass shootings

A student is far more likely to be involved in a shooting off campus. In fact, school shootings have declined precipitously since their peak in the early 90s. While the need to reduce the number of on-campus shootings to zero is an imperative, the reality is that placing officers in schools is not the solution and only leads to an increase in the arrest of students for child-like behaviors and creates a climate of distrust. Even though enhanced security measures, such as police and security officers, were “largely inspired by the school shootings in mostly white suburban schools, they have been most readily adopted and enforced in urban schools with low student-to-teacher ratios, high percentages of students of color, and lower test scores.”[2] The influx of police has come at the expense of adding much needed new teachers, counselors, or social workers.Proliferation of police

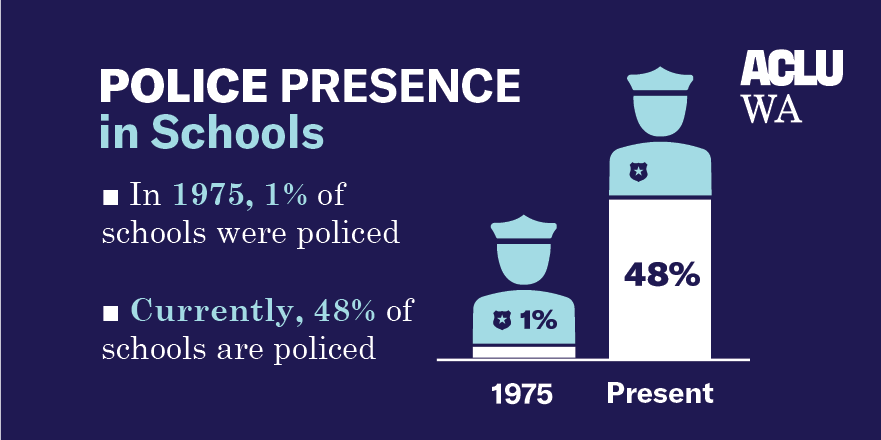

In Washington, 84 of the state’s 100 largest school districts have police officers assigned to schools.[5] This expansion of on-campus police comes with a hefty price tag. Schools pay, on average, $62,000 (and as much as $125,000) per full time officer annually.[6] In Spokane, public records indicate the Spokane School District paid over $1 million in salary and benefits for its school police officers.[7] Meanwhile, the Kent School District paid nearly $500,000 in salary to its officers.[8] Nationally, the Federal Government has invested more than $1 billion to subsidize the placement of police in schools, resulting in more than 46,000 SROs patrolling hallways.

Despite the billions in funding, evidence indicates the presence of on-campus officers does not prevent shootings. A study by Texas State University and the FBI examined over 160 incidents, including 25 school shootings. The study found that none of the school shootings were ended by armed officers returning fire. Rather, these shootings typically ended when the shooter(s) was restrained by unarmed staff or when the shooter simply decided to stop. If school shootings are the driving force behind SRO presence in schools, then this data certainly calls into question the effectiveness of this approach.

Crime is down, but arrests are up: How SROs criminalize youth behavior and contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline

Even though youth crime is on the decline — and has been, since the mid-nineties — and graduation rates are up, the myth that our children are criminal and violent persists. The data shows that the increase in arrests is directly correlated to the presence of SROs in schools The arrest rates for schools with SROs were 3.5 times the rate of those without SROs, and in some states the arrest rates are as much as eight times the rate of schools without.[9] Moreover, these arrests are a major contributor to the school-to-prison pipeline, which is a systemic process that pushes juveniles out of school and into the juvenile justice system. Once in this system, it is more likely that youth will be pushed out of school permanently, fail to graduate, be re-arrested, and end up in juvenile or adult prisons. The traumatic impact these interactions have on youth can lead to depression, anxiety, PTSD, and other mental and physical health issues.Policing in schools disproportionately targets students of color and students with disabilities

Exacerbating this problem is the fact that certain student groups are policed disproportionately. This is the case for students of color who are arrested or referred to law enforcement at significantly higher rates than their white counterparts. Moreover, students with disabilities are arrested or referred to law enforcement nearly three times the rate as their non-disabled peers.School officers are also more likely to use force against these groups. Pepper spray, tasers, pain compliance techniques, use of police batons, hitting, kicking, slamming, and choking are all tactics that have been deemed too harsh for detention facilities, and yet, these tactics are used against students in schools.[10]

The very presence of SROs blurs the line between criminal and youth behavior. It’s often assumed high arrest rates in schools are the result of student criminal activity. However, data shows students are often arrested for non-serious issues, including:

- Bad grades

- Tardiness

- Disorderly conduct like cursing

- Drug Possession for carrying a maple leaf

- Disrupting school through obnoxious behavior like fake burping or using fart spray

- Criticizing a school police officer or not following directions

These actions, while likely frustrating and distracting, are typical juvenile behaviors — behaviors that should end with a reprimand or a phone call home. However, in schools with SROs, these youth behaviors are criminalized. The impact of being constantly observed and judged makes it more difficult for youth to feel safe. It should be no surprise that exposure to this kind of treatment leaves students feeling alienated from their schools and distrustful of adults, creating a school setting that no longer feels safe.[11]

A Less Carceral Path to Safer Schools: Divesting from SROs and Investing in School Nurses, Social Workers, Psychologists, and Counselors

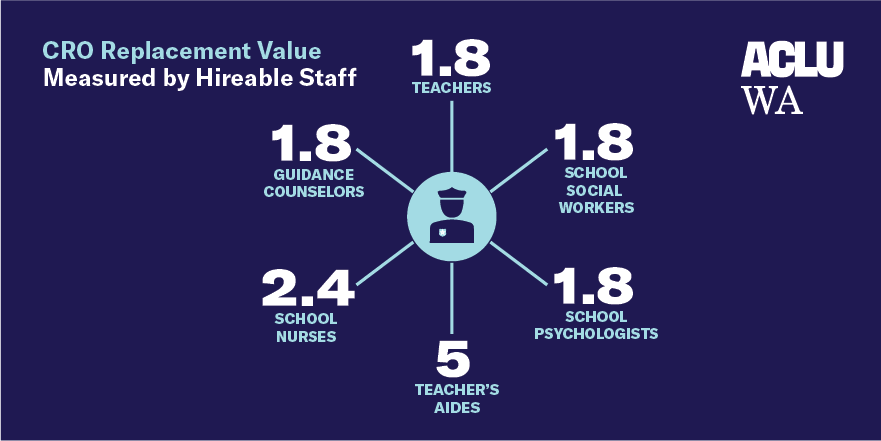

Fixing these issues requires investments — investing in counselors, nurses, social workers, and other professionals, and investing in communities. If we divest in police and remove them from schools, districts would have more resources to make these investments.There are trained professionals and organizations that can provide the right kind of support for individual students. However, there is not nearly enough of this support to meet the need in schools. While the number of on-campus officers has grown exponentially, 90 percent of students attend schools where the number of counselors, social workers, nurses, and psychologists do not meet the recommended professional standards.[12] The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) recommends a student to counselor ratio of 250:1. However, most states fall woefully short of meeting this need — including Washington, where public schools have a 482:1 ratio of students to counselors, according to the ASCA. Equally concerning is the fact that schools across the country lack these resources while maintaining a police presence in their halls.

- 1.7 million students attend schools with police but no counselors

- 3 million students attend schools with police but no school nurse

- 6 million students attend schools with police but no psychologist

- 10 million students attend schools with police but no social workers

SROs, no matter how well trained, cannot provide the same ongoing support as the above professionals can. Students who face barriers are the ones most often targeted for police intervention. They need a team of skilled professionals to provide necessary supports — not police referrals, arrests, and juvenile court. While cost is a clear contributor to a lack of or inadequate number of counselors, nurses, psychologists, and social workers, many districts only need look at their SRO/Policing budget to find the money.

How You Can Help

Large scale systemic change can seem daunting, but there are several ways students, parents, and any concerned individual can get involved:- ACLU Toolkit to advocate for removal of police from your school

- Support local legislation efforts to remove SROs or diminish their impact

- Support the National Counseling Not Criminalization in Schools Act

[1] https://news.northeastern.edu/2018/02/26/schools-are-still-one-of-the-safest-places-for-children-researcher-says/

[2] Nancy A. Heitzeg, Criminalizing Education: Zero Tolerance Policies, Police in the Hallways, and the School to Prison Pipeline. In From Education to Incarceration: Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline. p. 26.

[4] Id.

[6] Id.

[8] Id.

[10] Id

[11] Id