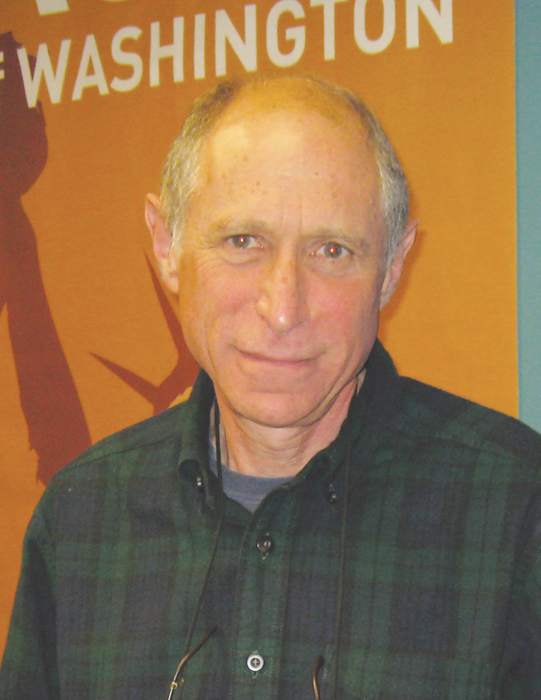

On May 10, 1970, a Washington state college student joined a chorus of anti-war voices by waving his version of the American flag. It featured a peace symbol – and it got him arrested under Washington’s flag-desecration statute. The student was convicted. The Washington Supreme Court did not grant his appeal. But in a landmark case (Spence v. Washington) won by Seattle attorney Peter Greenfield, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decision as a violation of the First Amendment.

Over the next 40 years, Greenfield would defend countless individuals whose rights were undermined or at risk. As a staff attorney with the legal aid organizations Evergreen Legal Services and later Columbia Legal Services, Greenfield defended the rights of low-income people. He represented those facing discrimination, disenfranchisement, and unfair treatment under the law – disabled people whose entitlement to government benefits was in dispute, domestic violence victims in custody contests, and individuals asserting constitutional challenges to police practices or other governmental actions. More recently, his work focused on the legal problems of the vulnerable elderly. And he was a leader on the ACLU of Washington’s Legal Committee for decades and served on the ACLU-WA’s board.

For his for outstanding and sustained contributions to civil liberties, the ACLU of Washington is honoring Peter Greenfield with the William O. Douglas Award, its lifetime achievement award. Greenfield is receiving the award at the ACLU’s Bill of Rights Celebration Dinner on November 4 at the Seattle Marriott Waterfront.

“Peter exemplifies the best tradition of advocacy on behalf of the disenfranchised. He has demonstrated a deep commitment to advancing civil liberties for all,” said ACLU-WA board president Jesse Wing. “He has tackled many difficult issues and done so with notable success, serving as an inspiration to people who believe that law should uphold justice.”

In an interview conducted on October 7, 2011, Greenfield talked about his career as a guardian of the Bill of Rights and what inspired him.

SR: What first attracted you to the issues to which you’ve devoted a lifetime of work?

PG: My family was quite dedicated to civil rights and civil liberties. My parents had been involved both in government worker union organizing and racial integration efforts in Washington D.C. in the early 1940s. I was active as a high school student in some integration related demonstrations organized by CORE (Congress of Racial Equality), and in the summer before I went to college, I was at the August ‘63 march on Washington. For the people who were there, it was an extremely moving event. It was a different kind of political gathering than I had been to before or after. It was a very large gathering, and extremely hopeful. I was 18 years old – just out of high school. And it made a very strong impression.

SR: What is the relationship between decisions made in court and public opinion, public demonstrations, like the ones you saw firsthand?

PG: There is a relationship. Courts in the United States, and especially state courts, have to take the public into account. But still, the Supreme Court tends to consolidate social progress rather than to be far out ahead of it. And in the long run there’s a lot to be said for that. Especially where one can see that the society is moving in a positive direction. If you look for example at the time of Brown v. Board of Education, there was rampant discrimination in the United States. But the majority of people didn’t support legally enforced segregation. It was a controversial decision, but the court wasn’t out of step with what most people in the country believed. It provided a kind of leadership that comes from consolidating and articulating a position.

SR: Apart from Spence v. Washington, what were the most memorable cases for you?

PG: One of the most satisfying cases that I did with the ACLU was Grant v. Spellman (1983). It was a case in which a King County police officer asserted a religious objection to being a member of a union that he viewed as racially discriminatory. At the time, there was a Washington statute that contained a contentious objector provision. But it was written in such a way that the State Supreme Court interpreted it to only apply to people who were part of an organized church with a specific anti-union tenet. Grant was a Christian, but not a member of a church – and certainly not a church that addressed this issue.

The interesting issue legally had to do with the fact that many kinds of beliefs can be characterized as political or religious, and there aren’t clear dividing lines. This confused people. But the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the State Supreme Court’s decision and sent it back. They held that if you have a religious contentious objection provision, you can’t condition it on being a member of a specific church.

The saddest experience I had with the ACLU involved one of the early Washington cases in which discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation reached the State Supreme Court. The case was Gaylord v. Tacoma School District (1977). He was a history teacher who by every measure had been an excellent teacher. He was never faulted for anything that he did. But somehow it came to the attention of the school administration that he was gay, and he was fired. Simply for that reason. And in an extremely insensitive decision, the Supreme Court majority held that there was no protection and the United States Supreme Court denied review. For the teacher, it was a very devastating injustice. For me it was decision that was very, very hard to accept.

SR: You’ve been involved in wide range of civil liberties issues. But is there one area that drives you more than the rest?

PG: My focus has been different at different times. In all of these issues there are common themes. For myself and for the people I love, I value having a significant measure of independence and liberty – and I want that for other people as well. I want to live in a society where the benefits of freedom and access to medical care, to sufficient housing, and income are shared, so that one can think about other things. I think that as a purely selfish matter, it’s a tremendous advantage to live in a society where you feel there’s some measure of social justice. Not just that you’ve been able to preserve some benefits for yourself, but when you go out in society you don’t see people in desperate straits. And of course there are a lot of people in desperate straits in the society in which we live. For many complicated reasons.

But things are also better in a lot of ways than when I first arrived in Seattle, or when my grandparents arrived in the U.S. I feel extremely fortunate to have been able to work within a program I felt very positive about for nearly 40 years, which is not an opportunity that everyone gets.

Summer Robinson is Communications and Events Coordinator for the ACLU of Washington.