It’s hard to succeed in school when you miss a lot of classroom time. Students who are suspended out of school or expelled are as much as 10 times more likely to drop out of high school. Students who are excluded from school are also more likely to have contact with the criminal justice system. This effect is so pronounced and widespread that it has a name: the school to prison pipeline.

In Washington, special education students are among the most at risk of being funneled into the school to prison pipeline because schools in our state suspend or expel them at a rate more than double the rate of discipline for their non-special education peers. Often, these students are punished for behaviors that are manifestations of their disabilities— conditions they cannot control.

It’s not just formal discipline; students are pushed out of school in insidious ways. Schools may persuade parents of special education students to agree to shortened school days for their children, depriving them of vital classroom instruction. Students with disabilities may spend a portion of a school day outside of class, in a hallway or another classroom, where they don’t participate in lessons. And parents of students with disabilities may get frequent calls to pick up their child from school as early as the first hour of the school day.

Over the past year, the ACLU of Washington has collected stories from dozens of parents who say their children were punished, excluded from the classroom, and pushed out of public schools in Washington for behaviors stemming from the child’s disability. Here are some of the stories they shared with us.

Ethan: Isolated, punished, and expelled because of untrained staff

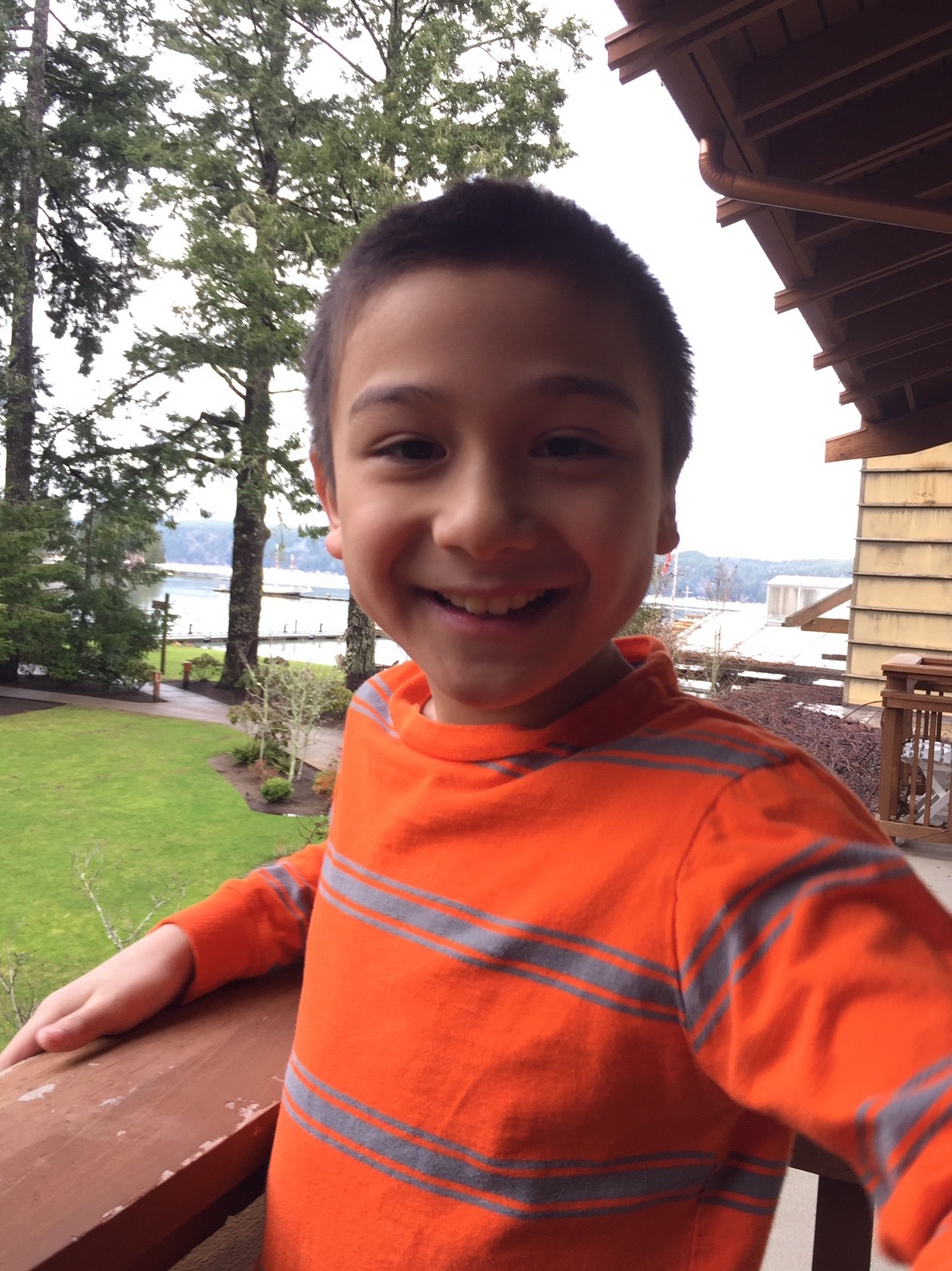

Ethan is a happy, active ten-year-old boy who is close to his parents and sister. The Bellevue School district has failed to provide him with the schedule, staff, or accommodations for his special needs that would allow him to be part of his community. Instead, Ethan is isolated, disciplined, and excluded from other students.

His mother Nicole says, “It’s not just Ethan. I have friends who have left this district and are homeschooling.” She wishes the district supported children to help them succeed, and that there was awareness in the school system about special needs students. She says that staff needs better training for special needs students and that they “can’t just be fearful.”

Ethan was diagnosed with autism, ADHD, and developmental coordination disorder at the age of four. Ethan has limited speech, so he uses gestures and touch to communicate. This can be misinterpreted as aggression. When overstimulated, Ethan requires breaks. After being placed in an integrated education program at his neighborhood preschool Nicole says he “did really well and excelled.”

Ethan thrived in kindergarten at a high functioning autism program until October 2012, when he broke his arm at school after jumping from a table. A paraeducator was sick that day, and there wasn’t enough supervision. From then on Ethan began to experience incidents at school, like having accidents and biting others. But the school did not inform Ethan’s parents of these incidents until June 2013, at an end-of-year meeting, and even then they did not provide incident reports

After kindergarten the school district wanted to send Ethan to a life-skills program. Ethan’s parents disagreed, knowing he could participate in school with the right staff and would benefit from being around other students, so Ethan continued in a special needs program offered by the Bellevue School District. Ethan was disciplined for having incidents, and was often placed in an isolation room with restraints. The school did not create any incident reports and implemented a plan that allowed school personnel to physically restrain Ethan. At the school Ethan had no access to PE or recess, and was with a paraeducator at all times. Ethan’s behaviors intensified.

Ethan’s parents noted that he was coming home with bruises as a result of the restraints. They began to check his body before and after school every day. While he stopped coming home with bruises in January, Ethan began having nightmares every night. Nicole says Ethan’s behavior deteriorated and “he just regressed.” In the summer of 2014, was diagnosed with PTSD.

When Ethan turned 8 he was too old for the autism curriculum at a private school he had attended, so his parents re-enrolled him in the Bellevue School District for the third grade. The district allowed 80 minutes a week for music and physical education as part of a life skills program with his autism trained specialist. In the fourth grade, the district increased his time to 2.5 hours daily, but with untrained paraeducators. Ethan became overly sensitive, injuring himself and grabbing and pulling others. The school district expelled Ethan because of his incidents, and because they lacked trained staff to interact with him.

The school district proposed Ethan attend a full-time residential program out of state. But this recommendation was based on psychologists and district personnel who had never observed Ethan, ignoring recommendations from Ethan’s parents, pediatrician, psychologist, therapist, and an Independent Education Evaluation authorized by the school district. They believe there should be a place for him, but that the school lacks specialists for students with autism. Ethan had missed 14 months of school in 2 years.

Ethan’s 8-year-old little sister Sophia does not understand why he cannot attend school with her. “It’s hard for us to see everyone in the neighborhood go to school and be part of community, and for him not to be included due to his disability.”

In Washington, special education students are among the most at risk of being funneled into the school to prison pipeline because schools in our state suspend or expel them at a rate more than double the rate of discipline for their non-special education peers. Often, these students are punished for behaviors that are manifestations of their disabilities— conditions they cannot control.

It’s not just formal discipline; students are pushed out of school in insidious ways. Schools may persuade parents of special education students to agree to shortened school days for their children, depriving them of vital classroom instruction. Students with disabilities may spend a portion of a school day outside of class, in a hallway or another classroom, where they don’t participate in lessons. And parents of students with disabilities may get frequent calls to pick up their child from school as early as the first hour of the school day.

Over the past year, the ACLU of Washington has collected stories from dozens of parents who say their children were punished, excluded from the classroom, and pushed out of public schools in Washington for behaviors stemming from the child’s disability. Here are some of the stories they shared with us.

Ethan: Isolated, punished, and expelled because of untrained staff

Ethan is a happy, active ten-year-old boy who is close to his parents and sister. The Bellevue School district has failed to provide him with the schedule, staff, or accommodations for his special needs that would allow him to be part of his community. Instead, Ethan is isolated, disciplined, and excluded from other students.

His mother Nicole says, “It’s not just Ethan. I have friends who have left this district and are homeschooling.” She wishes the district supported children to help them succeed, and that there was awareness in the school system about special needs students. She says that staff needs better training for special needs students and that they “can’t just be fearful.”

Ethan was diagnosed with autism, ADHD, and developmental coordination disorder at the age of four. Ethan has limited speech, so he uses gestures and touch to communicate. This can be misinterpreted as aggression. When overstimulated, Ethan requires breaks. After being placed in an integrated education program at his neighborhood preschool Nicole says he “did really well and excelled.”

Ethan thrived in kindergarten at a high functioning autism program until October 2012, when he broke his arm at school after jumping from a table. A paraeducator was sick that day, and there wasn’t enough supervision. From then on Ethan began to experience incidents at school, like having accidents and biting others. But the school did not inform Ethan’s parents of these incidents until June 2013, at an end-of-year meeting, and even then they did not provide incident reports

After kindergarten the school district wanted to send Ethan to a life-skills program. Ethan’s parents disagreed, knowing he could participate in school with the right staff and would benefit from being around other students, so Ethan continued in a special needs program offered by the Bellevue School District. Ethan was disciplined for having incidents, and was often placed in an isolation room with restraints. The school did not create any incident reports and implemented a plan that allowed school personnel to physically restrain Ethan. At the school Ethan had no access to PE or recess, and was with a paraeducator at all times. Ethan’s behaviors intensified.

Ethan’s parents noted that he was coming home with bruises as a result of the restraints. They began to check his body before and after school every day. While he stopped coming home with bruises in January, Ethan began having nightmares every night. Nicole says Ethan’s behavior deteriorated and “he just regressed.” In the summer of 2014, was diagnosed with PTSD.

When Ethan turned 8 he was too old for the autism curriculum at a private school he had attended, so his parents re-enrolled him in the Bellevue School District for the third grade. The district allowed 80 minutes a week for music and physical education as part of a life skills program with his autism trained specialist. In the fourth grade, the district increased his time to 2.5 hours daily, but with untrained paraeducators. Ethan became overly sensitive, injuring himself and grabbing and pulling others. The school district expelled Ethan because of his incidents, and because they lacked trained staff to interact with him.

The school district proposed Ethan attend a full-time residential program out of state. But this recommendation was based on psychologists and district personnel who had never observed Ethan, ignoring recommendations from Ethan’s parents, pediatrician, psychologist, therapist, and an Independent Education Evaluation authorized by the school district. They believe there should be a place for him, but that the school lacks specialists for students with autism. Ethan had missed 14 months of school in 2 years.

Ethan’s 8-year-old little sister Sophia does not understand why he cannot attend school with her. “It’s hard for us to see everyone in the neighborhood go to school and be part of community, and for him not to be included due to his disability.”

Court Case:

A.D. v. OSPI